Scott Hinkle completed the School of System Change Basecamp and Spark programmes in 2021. Here he shares insights and advice from entering the world of complexity to his current focus, including embodying systems change as an internal practice and three practical facilitation ideas.

Entering the world of complexity

A question that has stuck with me from Basecamp, shared by a fellow participant, is, “When did you first realise that you were working yourself to the bone — and even getting positive results — but that nothing ever changed?” Through my background of mediation inside the Chicago court system (a fascinating job) and working in international war zones for three years (South Sudan, Afghanistan), I learned that for every grievance, there is an immense iceberg underneath that is driving that emotion. Those two realisations drove me to enter the world of complexity.

In 2016, I moved to Wasafiri — a global consultancy, incubator, and institute — working as Team Lead for a research unit on preventing violent extremism in East Africa. The team at Wasafiri shared two things in common: one, we were all seasoned in international development and security; and two, we all felt that something needed to change but weren’t quite sure what it was. To resolve this, our leaders started reading about different methodologies to achieve transformative change. Out of these, systems thinking was the one that felt like the best fit for our culture and mission.

Reach good enough and getting going with action

Wasafiri’s Systemcraft framework for tackling complex problems was a result of our experiments with systems change. Team members would do high-level methodological research and then others would apply it on the ground, such as the research unit I was Team Lead on. We then came together to create the framework that is at the core of how we drive change today. There are two important learnings I’d like to share from this experience.

The first is the focus on action: we learn by acting on the system, observing and then adapting. Creating action early on is important otherwise people and communities get disheartened. My suggestion when trying out new systemic approaches is to hit good enough and then get going (with action). The second learning is to adopt an experimental mindset. I tend to use ‘experiments’ instead of ‘projects’. This shift in mindset helps us let go of an approach if it’s not working, meaning we can adapt and act in agile ways that are necessary when working with complexity.

Basecamp: systems change is an internal practice

When I joined the Basecamp programme by the School of System Change in 2020, I had been working in systems change in some manner for around four years. I gained a lot from the course that I have integrated into my consultancy work, and really enjoyed the experience. So much so that I joined another School programme specifically focusing on facilitation skills — Spark — as I discovered that a key part of my practice is training people in facilitation.

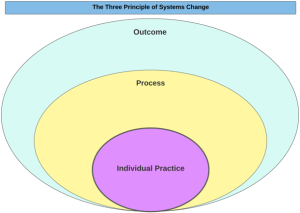

A realisation shared by another participant at Basecamp that lives in my mind is, ‘I’m the system that needs to change first’. This emerged from three principles introduced on the course around the key question, ‘what is systems change?’:

- Systems change is an outcome

- Systems change is a process

- Systems change is an internal practice

The first is the most clear: systems change as an outcome relates to when a new pattern emerges and sticks. Ideally, this is the desired change of the system. The second principle, systems change as a process is all about doing things differently with a focus on how we work and how we approach creating change. I understood and practised both principles before Basecamp. The third principle however — systems change is an internal practice — was completely unfamiliar to me.

Systems change as an internal practice is all about the personal skills, behaviour, and way of being that allows us to help others deliver change. What is often missing from systems change work is embodying the spirit of what systems change is. Charlene Collison, my coach during Basecamp, encouraged me to consider my role beyond a leader in the process to a leader in ‘the embodiment’ and personal practice of those I am supporting to create change. To help others deliver meaningful, lasting impact, we ourselves have to practice what we are asking of them. This is one learning from Basecamp that I have integrated into my consultancy work, asking myself and the people I work with, ‘How is your daily practice changing?’

Spark: capable and compassionate facilitators

The second programme I completed with the School of System Change was Spark. This course allowed me to sharpen my facilitation practice and develop a facilitation guide for our systems change work with the Reach Children’s Hub in Feltham.

From my experience, the unsung heroes of successful systems initiatives are capable and compassionate facilitators. Skilled facilitation is often underappreciated, and most people I work with learn it on the fly with little to no training. Part of my work at Wasafiri is training people on the go how to facilitate; I often sit in on groups to observe, noting what can be improved.

From Spark, there are three facilitation ideas that I share with people:

- Less prep, more presence

- More inspiration, less information (80/20 rule)

- When there are multiple directions you could go, share the dilemma

‘Less prep, more presence’ encourages us to be present in conversations we are facilitating, and relates to embodying the spirit of systems change. I often find that inexperienced facilitators will, understandably, overprepare. This results in more of a presentation than a facilitation and can mean you are too focused on your own notes to support the conversation to emerge the way it wants or needs to.

‘More inspiration, less information’ relates to the 80/20 rule (Pareto principle). When you are trying to mobilise people to work collectively and take action, they need to be inspired, not informed. You want them to have a meaningful experience together. This is how to induce action, not a packed slideshow presentation.

‘When there are multiple directions you could go, share the dilemma’ reminds us that as facilitators, we don’t have to make all the decisions. We are not there to control, but support. Instead of making the decisions on your own, ask the group for their thoughts. Share the uncertainty with the group, and everybody can decide together, creating buy in for the direction of the conversation.

To gain an insight into more of the course content, I recommend reading this blog by Anna Birney, Director of the School, all about knowing, feeling, and facilitating the patterns of systems conversations. This isn’t something I actively use with the people I work with, but it definitely influences my practice, living quietly in the back of my mind. Thinking about the patterns of a conversation can provide an indicator of the mood of the group. For example, is the conversation diverging and converging, or are you going in a cycle, or perhaps you are going deep, or shallow? Visualising these patterns and connecting feelings to each helped my practice. Consider the differences in what it feels like when you’re thinking creatively or going deep in a conversation, and use those feelings to guide your facilitation practice.

My current question and focus

As I close out for today, I’d like to pose a question and a ‘call to arms’, so to speak.

Key question: How do we maintain systemic initiatives that live inside of rigid hierarchical institutions? In May, I presented at a conference for the Systems Innovation Network entitled, ‘Practicing Systems Change in a World not Built for it’, which captures how I and my systems change partners feel at times. I often work with a small group of dedicated people who put in the time and resources to shift the way they think about and work on their critical issue, which requires a process of Unlearning. Once they start working more collectively and emergent, they see and feel the value and want to keep working that way. However, this new group of systems actors are almost always embedded in larger institutions (INGOs, corporations, local authorities, etc..) that don’t work that way and are often resistant to it.

My current answer is to demonstrate the value of systemic ways of working on another complex problem the institution is facing. For the client, creating and maintaining a collective and adaptive capability might seem like a lot of investment (time, money, personnel) for one particular problem. However, showing that the capability can be used effectively on multiple complex problems is a solid way to get buy in and participation. A powerful example of this is from our work with Reach Children’s Hub, who set up the systems initiative to improve children’s outcomes, and then used it on a refugee crisis that resulted in strengthening community resilience. If you have any thoughts on this from your own experience and organisation, please reach out or share a comment.

My current focus, Building Communities of Action: Family, Children and Community Hubs. Cities and towns across the UK are experiencing diverse and dynamic shocks, from the cost of living to the mental health of young people in school. Communities are seeking opportunities to make autonomous decisions to respond to their current needs while becoming more resilient in the face of future challenges. This has resulted in a push across the UK to use the power of communities and integrated services for transformative change, such as the rollout of Family Hubs. Wasafiri sees this as an amazing opportunity for systems-based work and for people working in the systems change movement to get involved. For example, Family hubs are about co-locating services, but we know that simply putting everyone in the same building isn’t going to get people working together effectively. Instead, people need guidance — from facilitators and coaches — to shift to collective and adaptive ways of working for transformative change. Thus, I ask practitioners to lean into this space and please reach out if you know ‘a hub’ who may need some guidance.