I find pattern spotting deeply satisfying as a practice. It helps me work with complexity rather than trying to simplify it, it reveals rhythms and structures that can support deep change work, it awakens my curiosity and creativity and quietens my rational brain’s constant quest for answers. At best it reminds me how much the world we live in is alive, and brings a 60s wallpaper sort of joy to very challenging work.

In systems change work, the term “pattern” comes up a lot. We refer to “pattern spotting” as a practice that can help understand the dynamics that characterise a complex system. We ask about “patterns of behaviour” and how to explore their deeper causes. We can even define systems change as “the emergence of a new pattern”, as an outcome where the “pattern of a system has changed”.

However, working with budding and seasoned systems practitioners over the last few years has led me to believe that we are not all putting the same thing behind this magic word. My unsatisfactory attempts to translate it into French (I live and work in the South of France) have also shown how much can be conveyed by this one word. If we want to collectively develop this practice as an effective way of understanding and engaging with systems to create change, we might want to delve a bit deeper into the multiple meanings of “pattern”. This article is an attempt to do that by bringing some structure to the way we think about pattern in the context of systems change.

Systems change pattern spotting: from two dimensions to four dimensions

Pattern recognition is a core ability of the human brain, and that of other animals, whereby information received from the environment — through all the senses — enters the short-term memory and is compared with content stored in the long-term memory. Finding similarities between what we experience now and what we have experienced before enables us to process huge amounts of information in an effective way; we do not need to analyse every piece of data because we can rely on patterns to understand what is happening and what is likely to happen next.

Pattern recognition is necessary for understanding language, recognising people we know, enjoying music and art, engaging in logical thinking and reasoning. This ability draws on several different cognitive processes which allow us to engage with the complexity of the world around us. In this article I am not sharing content around these cognitive processes (Wikipedia is a good starting point for this), but rather a way to think about how we use this ability in systems change work.

I am proposing a structure for exploring “pattern” that is based on our understanding of dimensions. This has helped me tease out some subtle differences system change practitioners are referring to when they speak about pattern spotting. As always, the framework I propose here — from two dimensional to four dimensional patterns — is not a description of reality but a way to engage our visual and geometric cognitive capacities when working with complexity.

Starting with 2D

When thinking of patterns we often think in two dimensions — a motif repeating across a flat space, such as a pattern on a wallpaper. As facilitators of change processes, we might also use two-dimensional pattern-spotting in a conversation or workshop setting when we’re looking to cluster ideas, matching like with like. Here although the setting is alive and three dimensional, the way we’re playing with pattern is effectively in a ‘flat’ space as we organise components into clusters of similar content, or along a spectrum with two polarities.

This is a great skill to strengthen when looking at the world: natural forms are brilliant for repeating patterns, and graphic designers generate wonderful visual shapes in wallpaper and typography. Mathematical patterns can also be a way to explore what I’m calling two-dimensional patterns, looking at sequences of numbers and finding the way they’ve been designed. Or exploring geometric patterns and shapes

However, this is just the starting point for recognising patterns in systems.

Moving to 3D

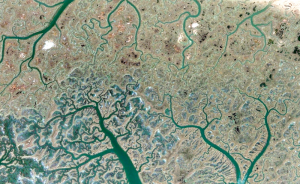

Beyond this two-dimensional focus, we need to layer on the ability to see patterns across scales and contexts, to work with the interconnected and complex nature of the world. We can understand the living world as being fractal, with shapes that repeat across scales like a fern leaf.

adrienne maree brown has a chapter on fractals in her book Emergent Strategy, Shaping Change, Changing Worlds (2017). She invites us to:

“Tune into the prevalence of spiral in the universe — the shape in the prints of our fingertips echoes into geological patterns, all the way to the shape of galaxies. Then notice that the planet is full of these fractals — cauliflower, yes, and broccoli, ferns, deltas, veins through our bodies, tributaries, etc. — all of these are echoes of themselves at the smallest and largest scales.” (pp51–52)

So when exploring systems, we look for core patterns that are showing up across scales. We ask questions such as “How is what is going on at a small level in my team, in this organisation, mirroring or reinforcing a problematic characteristic of the wider sector we’re part of?”

This can be trickier than finding 2D patterns because it’s often harder to see polarities or similarities when we broaden the boundaries within which we are inquiring. Things that might feel quite materially different because of scale — user experience of getting on a train, where people coming from all over the city converge in a station and then get filtered onto their respective trains, with ticket barriers etc. and the organisation of the train network at a national level where regional services converge on big cities and often on the capital in a “all roads lead to Rome” pattern [check this example, centralised energy might be another interesting one] — can be understood to have a fractal quality. To see this, we need to practice being able to ‘zoom out’ and look at more complexity, while holding onto a pattern we’ve identified and are familiar with when we ‘zoom in’.

We might also start looking for patterns across different contexts within a given system or challenge. For example, I worked with a team looking at how to foster more collaboration with groups involved with marine conservation and the definition of priority marine conservation zones. After a lot of thinking about barriers to collaboration, as a group we identified a pattern that was showing up across the piece. The government process for engaging diverse local stakeholders around marine conservation issues was essentially extractive: asking for insight that then just got fed into an opaque decision-making process where the local people had no agency. This mirrored the wider relationship to the sea as a whole, equally extractive — people extracting fish, dredging up sand for the construction industry, thinking of the sea as a leisure space — where the sea’s intrinsic agency as a living system was not brought into the equation at all. Identifying this pattern between the wider issue of our relationship with the sea, and the governance culture and process in place around marine conservation, opened up avenues for creative thinking about how to seed positive change.

Exploring 4D

We have looked at two and three-dimensional patterns, and yet when we are doing systems change work we also need to stretch to four dimensions — to include patterns and change over time.

One big difference between wallpaper and patterns in the living world is that the former, despite some psychedelic motifs that might seem to move, are static, whereas the latter are in constant motion, changing over time. This is essentially because they are relational. If we move beyond the wallpaper pattern seen as an image of forms organised in a certain way on a flat surface, to ask ourselves which relational patterns it is involved with, things come alive: crazy 1960s wallpaper consistently make me smile, and consistently make my mother cringe (which then makes me smile!). These are the patterns of systems change — dynamic patterns of behaviour in the world. Donella Meadows shares the importance of looking for these:

“Systems fool us by presenting themselves — or we fool ourselves by seeing the world — as a series of events. […] We are less likely to be surprised if we can see how events accumulate into dynamic patterns of behavior. […] The behaviour of a system over time — its growth, stagnation, decline, oscillation, randomness or evolution. […] When a systems thinker encounters a problem, the first thing he or she does is look for data, time graphs, the history of the system. That’s because long-term behavior provides clues to the underlying system structure. And structure is key to understanding not just what is happening, but why.” (Donella Meadows, Thinking in systems: a primer, 2008, pp88–89)

Pattern recognition as a cognitive ability is developed in order to predict what is going to happen next through remembering associations of events in the past, so we can flow with what is going on. With systems change work, we are not only looking for patterns of how things are predictable and repeat, but also how things are changing — what is the pattern of change? We think about how things have come about to be the way they are, and what relational elements are affecting how change is happening.

Systems change practitioners often invite us to look at the interactions between different forces to deepen our understanding of the patterns of change. Here are a few of the ways I have learnt to develop this practice of what I’m calling 4D pattern spotting, alongside practitioners we work with at the School of System Change.

Interacting patterns of structure and process

Bill Sharpe’s “holism with focus” exercise from his book Three Horizons: The Patterning of Hope (2013) has us understand the evolution of pattern in the world over time by exploring cycles of flow and structure. He invites us to look at a tree:

“What you immediately see is a structure of trunk, branches and leaves. What you cannot immediately perceive, but know to be the case, is that the tree is living and growing by drawing up water and nutrients from the ground, and capturing sunlight in its leaves to drive the process of photosynthesis. […] The structure of the tree configures the processes by which it lives, and those processes build and maintain the structures.” (pp35–36)

Tuning into the dynamic relationships between structures and processes is a core skill that is used during a Three Horizons futures process, helping us look for adaptive pathways towards a desired future.

“There is so much information around us all the time that we cannot possibly pay attention to all of it, or think about where it might lead. Only once we have tuned into a longer-term perspective and primed ourselves to see the patterns in play does the small act acquire big significance as a harbinger of things to come.” (p40)

A dance between patterns and events

Jean Boulton’s approach to embracing complexity invites us to look at the dance between patterns (established and contextual ways of being in the world, which I would call two-dimensional and three-dimensional patterns here) and events (convergent moments of change with the power to disrupt patterns). This can help us to understand and influence the non-linear evolution of systems over time. In the book Embracing complexity: Strategic perspectives for an age of turbulence (2015) we read:

“The future is a complex combination of (a) the effect of current patterns, which can be studied — at least to some degree — scientifically and analytically, and (b) the effect of particular events or variations at particular times and places. These two factors — enduring patterns and specific events — through interacting together, shape what happens.”(p31)

This is an invitation to broaden our view beyond the pattern, to the non-pattern, specific and contextual signs of other things happening: “It is the detail and variation coupled with interconnection that provide the fuel for innovation, evolution, change and learning.”(p29)

Sensing into essence patterns

Ben Haggard and Pamela Mang’s practice of regenerative development has us working to understand essence patterns that influence how complex living entities evolve and change in response to a dynamic world, while still staying true to their essence. Seeing these patterns requires us to engage with deeply contextual thinking, for example in understanding places as living systems:

“It is possible to discover the ongoing and distinctive core patterns that organize the dynamics of a given place. These core patterns are the source of its recognisable character and nature — its essence. They influence the complex relationships that produce its activities, growth and evolution. When seeking to identify these core patterns, Regenesis asks three questions: How does this place organize and renew itself? What does it consistently pursue? What value does it generate as as result?” (Regenerative Development and Design, 2016, p49)

I have tried to articulate my attempts at applying this sort of approach to living systems beyond place (see article here), and certainly find that using a pattern mind to do this is key.

Developing your pattern-spotting practice

Like all systemic practices pattern spotting is a skill to be reawoken, reframed, practised and developed all the time. I say reawoken because we all have a capacity for pattern recognition from our earliest childhood as we discover the world and the people around us, and this is something we can become more attuned to again as a way of being in the world as much as a new skill to acquire. As with all practices, we improve muchly with small daily honing of pattern spotting skills as well as (more than?) with chunky dedicated time. Here are some ways some of us at the School of System Change practice pattern spotting in our daily lives and work, with techniques and frameworks from across the field of systems change and beyond:

- check-ins where we mirror back the pattern of the whole to the group

- playing with multiple cause diagrams / causal loop diagrams, zooming out to see the deeper pattern that drives the dynamics of a system

- seeking essence pattern when engaging with new people and organisations

- visual note-taking

- learning to play music (again) and crafting playlists for online learning sessions

- writing poems, or finding poems for important learning moments

The joy of learning in a world that is becoming

For me, the joy of this practice is in the sweet spot between comfort — recognising a pattern is deeply satisfying and reassuring — and learning, sparking new connections and neural pathways. As Tyson Yunkapora so beautifully puts it: “if people are laughing, they are learning. True learning is joy because it is an act of creation.” (Sand talk, 2019, p112) He goes on to distinguish between two kinds of joy: “One is characterised by light-heartedness and the other is marked by fierce engagement and deep concentration.” For me, pattern spotting can be both: light-hearted (as in 60s wallpaper) and also a fierce engagement with what is needed from us in the world right now, for our work in systems change. As Ben Haggard and Pamela Mang write,

“An ability to discern the patterns around us is key to honoring and working with complexity. […] It is this way of seeing that enables us to engage with a world that is becoming.” (p210)