Roberta Iley is the acting Associate Director for UK/Europe at Forum for the Future. Here she looks back on how participating in the School of System Change Basecamp programme in 2019 has impacted her work transforming food systems.

When I joined Forum for the Future, I knew I was going to have to quickly get up-to-speed with ‘systems change’ approaches and tools, given the organisations’ core ethos. I joined the School of System Change’s Basecamp programme with the advantage of knowing that my whole job was to implement this kind of thinking. I already felt pretty confident in my understanding of the topic — Forum had hired me after all — and I was glad to be working for an organisation that I saw as being more ambitious and cutting edge.

I had the familiar mantra in my mind — we can’t change how we produce food (my particular area of interest) just by relying on individuals to change their behaviour and making different dietary choices, we have to go beyond that to change the structures — policy, finance, marketing that shape and incentivise that behaviour. Like many others, I felt that the urgency of climate change needed nothing short of a drastic mainstream shift, requiring change at scale. This in my mind was the essence of systems change and the defining feature of whether or not you had your eye on the bigger picture and an ambitious strategy for change.

At the time I was leading our multi-stakeholder collaboration, the Protein Challenge 2040, a collaboration between a number of different businesses and NGOs working on the future of protein. Collaborations are a key feature at Forum — after all, if you are going to influence the big societal structures beyond any one organisations’ control, you have to work together. This topic had exploded since Forum started its work back in 2014/15. Not only were a number of high profile papers being published highlighting the damaging effects of livestock production for the climate but it also felt like we were on the cusp of a societal shift to change our protein consumption in Western countries and eat more of the exciting new alternative protein products coming onto the market.

I felt glad to be working on such an important topic where it felt like there was real potential for making a difference and driving systems change. I was keen to see how our collaboration could go beyond what sometimes felt like niche pilots that we were running (such as on how to make new plant protein products available and desirable as part of the US School Lunch Program) to driving impact at scale and influencing the broader agenda for change, e.g. advocating for policy change on food subsidies. I felt this would be key for regaining some of the momentum we had lost in the collaboration. I had an inkling that we were at a sink or swim moment — either we could step up and work alongside the ‘big boys’ — other high profile initiatives now working on protein and food systems — or we should step back and acknowledge that our contribution wasn’t needed anymore.

In going through the Basecamp programme, my perception of how we could contribute to change in the next phase of the Protein Challenge 2040 evolved. Fundamentally it challenged my view of what ‘system change’ is, and highlighted some traps that I know I often fall into when getting particularly grandiose about Forum’s purpose to catalyse systems change:

1. There’s no magical formula or ‘right’ answer, we have to experiment

At times when people talk about systems change, there is a sense that if you know everything there is to know about a system — then you can identify the key levers for creating change, figure out the root causes and avoid any unintended consequences. It’s easy to be beguiled by the idea that there is a ‘right’ answer out there waiting to be found if we put in enough effort.

We often form stories about how change has happened in the past to help meet our own need for a logical link between cause-and-effect. Yet, it has long been recognised that by their very nature, the systems we are part of are not even just ‘complicated’, they are complex and emergent (Jean Boulton’s work on complex systems really opened my eyes on this one). This alone — not to mention the fact we are entering a new realm of climatic and societal change that (as, of course, with anything in the future) we have never experienced before — helped me to realise that we are never in a position to analyse or predict the perfect approach to driving change.

So the first thing I had to let go of was the idea that I could identify the ‘right’ strategy for the Protein Challenge 2040 going forward. Instead, I focused on what strengths we brought as people and as an organisation that could contribute to the challenge — and how we could test a model that was agile — and which we could experiment with, and rapidly adjust. This was the beginning of the Action Sprint model we are now testing — a rapid fire, time-bound process, focused on bringing people together around a particular protein challenge question.

2. You can’t influence change ‘out there’, without changing yourself

It feels like a real cliché to say, ‘be the change you want to see in the world’. In contrast to the common framing that ‘it’s not about individual behaviour change, we need whole systems change’, the further I went through Basecamp, the more I came to the view that it is a false distinction. Creating change is as much about your own personal journey of change as it is about trying to influence ‘THE (mythical!) SYSTEM’.

There is a real aversion in the sustainability sector to the idea of doing too much navel gazing when the challenges out there are so real and urgent. I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard that what we need is change at scale and that going all hippy and use words like ‘mindset change’ or by getting egotistical and promoting things like self-reflection, risks undermining the drive for impact. Yet in the same way that people only change when systems change; systems only change when people do. All of us — in everything we do, every decision we make, and every conversation we have, are creating the system we see around us. It is both terrifying and electrifying to recognise the reality that the ‘system’ around us gets recreated every day by our actions (thanks Bill Sharpe for that laser insight).

In our protein work, I realised that there was a real risk that by just focussing on creating pilots, scaling interventions and advocating for others to change structures and processes, we were at risk of perpetuating inaction for those of us actually involved in the collaboration. Going forward, we are focused less on creating new things ‘out there’ and more on processes that support participants to reflect on shifting their own actions, behaviours, interactions and mindsets — and of course, that includes reflecting on how Forum for the Future, and myself, needs to change to be part of creating a sustainable protein system.

3. The key question isn’t always ‘what’ needs to change, it’s also ‘who’ shapes the change

The world never stands still. We are all in a constant state of change and flux (even if it doesn’t always feel like it…).

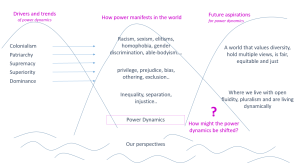

When I started seeing the world around me as forever evolving, I started to think less about ‘creating systems change’ and more about who is currently influencing or shaping the trajectory we are on. Exploring the world through the lens of whose actions get noticed, who currently feels agency, who is in a position of feeling able to exert power, and who is involved in decision making, was an eye-opener for me. It is a common refrain in the systems change world that ‘systems aren’t broken’, they are well optimised for the goals we want to achieve. The question becomes, whose goals and needs are driving the current direction of the system?

This thinking led me to explore whose voices are currently being heard around the protein transition (answer: often a predominantly middle class, white and western community, myself included!). What would happen if we shifted into listening mode and worked to elevate different people and voices, using our strength as a facilitator to bring people together with very different perspectives? Convening diverse cohorts of people is now at the core of what we are testing in our new Protein Action Sprint model.

Even in trying to boil down my thoughts into those simple three points (yes — I couldn’t help adhering to that particular custom), I know that I have skated over crucial nuance and complexity — something I aspire to get better at understanding and conveying.

So perhaps if there’s one thing I learned from my experience with the School of System Change it’s that you can’t ‘learn’ or ‘get up-to-speed’ on systems change. Like everything, exploring how change happens is part of a never-ending, human desire to better understand the world around us and derive meaning from it. We may never get there but I for one am enjoying putting on a new set of glasses.