This is blog three in our series created to complement Stepping Into Systems, our introductory short film series on systems change. In blog one, we speak about the process of creating the film series, which involved in-depth interviews – yarnings – with a diverse range of systems change practitioners. In this blog series, we give space to some of the rich and beautiful sharings from those yarnings. This blog pairs with the second film in the series, 'The Importance of Systemic Worldviews', which explores how our worldviews shape systems. Watch the film here.

Simply, our worldviews are how we see the world. They are the frames through which we understand everything, shaping our sense of self, our relationships with others, and our behaviours and beliefs. There are, of course, many and diverse worldviews. Over the course of the yarnings with the elders of systems practice, we heard of the diverse lineages that shape each of their worldviews and systemic practices, as well as the importance of considering people’s worldviews in the systems change work.

Maya Narayan recites a potent quote from writer Anaïs Nin: “We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.”

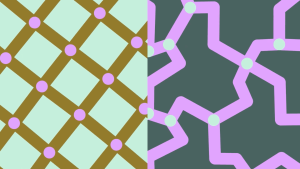

Individual worldviews repeat within our families, communities and societies, creating patterns. The patterns we understand can reinforce our worldviews and entrench certain beliefs for us as individuals, collectives and societies, repeating at scale, like fractals, from the minutiae to the mega.

It can be difficult to discern the patterns that live within us, but this is the work of systems change. Pervasive worldviews that champion rational, mechanistic thinking and logic and thrive on narratives of dominance, subjugation, oppression and separation govern many of our societal and global systems. These worldviews fail to recognise the systemic nature – nestedness, interconnectedness, aliveness and emergence – of all things.

Ben Haggard explains that the pervasiveness of mechanistic framing manifests even in how we see ourselves, in “the way we ubiquitously use machine metaphors to describe ourselves. ‘Oh, I've been programmed to think that way,' or ‘My hardware needs a bit of a tuneup'. We literally describe our own bodies and our own selves and our psyches as computers or machines … Most of my thinking about systems is in the context of living systems. Even if I'm thinking about things that we don't usually think of as being alive, like geological systems, in the sense of the universe unfolding and evolving continuously. They are living systems or can be thought about as living systems.”

Being systemic is our nature. We are born systemic beings. Systemic ways of knowing and seeing the world have always been with us. Many Indigenous cultures around the world are rooted in systemic worldviews, arising from a deep connection to the land and place. Eruera Tarena explains:

“Our Māori worldview is whakapapa, or genealogy. So our culture is based on the ability to recite our lineage. So as people, we are families, we are sub-tribes or clans, we are tribes, and everyone can recite their lineage and knows how we interact with each other. When you take that whakapapa backwards further, we can trace our descent from the gods, and through that we can connect [with everything], because it's not just people that have a whakapapa, or genealogy. We can trace that to our natural environment, to our landscape, and even intangible things like knowledge and thought have a genealogy. It shapes more of a systemic view of interconnection and interdependency where what happens to a natural landscape impacts the people. People can recite these genealogies, they can recite creation traditions that talk about how the land rose up from the oceans, they can recite the genealogies of fish, of mussels, of all our different birdlife. All of that is really around connection and interdependency.”

We asked all the practitioners about their lineages in their systemic practice. Melanie Goodchild says, “My first lineage [of systemic practice] comes from being Anishinaabe, from that perspective of my ancestors here on Turtle Island, which is North America, and we have all kinds of teachings.” One of which, she describes, is “about the interconnectivity of all beings … which is really a deep systems perspective.” She has other lineages that inform her thinking and practice, including “studying systems thinking, systems dynamics and complexity in my doctoral studies.”

She continues: “I think about what I've done to reconcile those very distinct lineages. One comes out of a predominantly academic, intellectual lineage, coming out of the enlightenment within science, with compartmentalisation and reductionism. [...] I saw a resonance there, but I felt that I needed to decolonise it because it was very anthropocentric.” Noting the paradox, she explains, “It's for human beings but to be more interconnected [with human and more-than-human beings]. So what it aspires to is holistic thinking or irreducible wholeness. But how can we have irreducible wholeness if humans are [considered] separate, and not only separate but higher than [their more-than-human kin], in a hierarchy? So transcending binary thinking and hierarchical thinking are two of the main ingredients of what I try to cook up when I take people out onto the land.”

Also experiencing a disparity between various schools of systems-based research and systemic sensibility, Lauren Hermanus echoes a similar sentiment: “There is a tension that emerges when systems and complexity science is applied to social phenomena. Within Western thinking, early attempts to do this borrowed the models, language and insights directly from natural sciences and mathematics, and, I think, also came with a real desire to predict and control the world more effectively. So, on the one hand, the ideas of systems and complexity opened up new ways for us to think about and make sense of things in the Western world that emerged from its formal imperialist age and the chaos of its own so-called ‘World Wars’. But the tension arises because complexity as a phenomenon is an experience of excess, with respect to our sense-making facilities and tools, that has been articulated across so many different ways of thinking beyond Europe, and across disciplines, theories and areas of life. [...] I think that human beings have always been concerned with how we approach and make sense of that which is excessive, overwhelming and awe-ful. That which renders us full of awe.”

She continues: “I think awe is a good emotion to sit with when you're working on systems change because it's almost like a meta-emotion. It brings lots together: wonder, excitement, and anticipation but also fearfulness and a sense of smallness. So, for me, there is an inherent discomfort with the language of complexity and systems as they are brought to social systems, to social phenomena, let's say. I think that that impulse to reduce, predict and control is so alive and well and embedded in so many of those approaches that I think that we skip past the deep and profound uncertainty and the awe in ways that undermine our sense of responsibility in the work that we do, in changing these things we call systems.”

Habiba Nabutu states, “I don't accept that there is such a unifying thing that's called systems practice,” cautioning how the language of one lineage seeping into conversations attempting to encompass multiple lineages bears the markers of history repeating, with colonisation. “‘Systems practice’ has its own logic in European thinking. I think if I was coming from an African perspective, it would be completely different.”

She continues: “I think the [terminology of systems change] comes from the Euro-American traditional lineage. [...] So those definitions taken up by a lot of people like Donella Meadows and all these others, I am fine with; that is really around how do we look at things much more holistically. But that's within that tradition. I reject it when it starts to be applied to the rest of the world.” She explains that “in many spaces, we think that we are learning when, in fact, we are taking on European assumptions and presuppositions about the nature of reality. And those are very different from African assumptions and presuppositions about the nature of reality.”

Ana Lucia Castano explains her lineages of systemic thinking, paying homage to “the movement of the decolonial thought in Latin America … and how to think about that in relationship to the global north, in relationship to the global south, in relationship to our economic systems, our meaning systems, our land management systems. All of this approach to really understanding how we are the outcome of a series of relationships, and how we can start thinking about ourselves through thinking about how we relate to different things, how we relate to knowledge, how we relate to land, how we relate to traditions and ancestral cultures.”

She speaks of “the Amazon people from Colombia and the indigenous peoples with whom I worked, who very early on influenced me to understand other types of relational views of life and … the way they think about themselves, the way they think about their learning process, the way they think about their future."

"There’s a beautiful story that comes from the myth of creation of the Guambiano people in Cauca, who associated the land, the territory, with time. For them, everything is about walking the land, walking through the landscape, and when you walk, you're looking forward to yourself, and what you're seeing is the past that your ancestors have already built for you. So the future is not in front of you, it's at your back. It's everything you're not seeing as you walk. It's everything that's coming behind you. It's walking behind you and taking you, and you can't see it. What you're seeing is actually your path, which is contrasted a lot with our Western narrative about how the future is something that is in front of us in this linear view of time.”

Our understandings of time are also framed by our worldviews. Melanie talks about time and thinking relationally beyond the anthropocentric: “The elders define what we're doing in terms of systems change and how that change happens as clearing the pathway for the beings yet to come. And so that is the practice of what we might call building the container, creating the conditions for the emerging future.”

Further dispelling notions of linearity in the context of time,Tatenda Nzingha Mazowe discusses the concept of “ancient futures” and “what innovation looks like”. She speaks of reclamation: “Black reclamation, intellectual reclamation, spiritual reclamation, even reclaiming our position in history is part of systems change; it's done through art, it is done through people releasing dystopian ideals that have been projected about the future. Embracing protopia, embracing identities that aren't devoid of culture but that are culture-full.”

As innately systemic beings, embodying systemic worldviews isn’t just about learning; it’s as much about unlearning, re-learning, reclaiming and reawakening who we are. Juanita Zerda shares, “I've been on my own journey of understanding my lineage or rescuing my lineage, because as an immigrant, I arrived to the USA, had to start from scratch, and I wanted to do well. A lot of what I did was adapt and learn the paradigms that I need to function under. […] Through the racial equity movement, I started to question my own identity and say, ‘Okay, what do I think about systems? What is a system?’ Honestly, I went back to my Latina heritage, and for us, for me, the system is the community. The system is my family, the system is the community within which my family exists, and the way we relate to each other. That is it. I started rescuing those parts of who I am. Those parts of who I am that I actually sometimes hate because [they are] too emotional, too vulnerable.”

The emotionality and vulnerability that Juanita speaks of lay the ground for healing from violent, oppressive and hierarchical systems and power dynamics. Talking about aspects of her work, she explains the power of healing circles:

“Sitting in a circle, not having edges, being all at the same level already changes the way that you're starting to perceive each other. It establishes from the get-go a horizontality. We tend to sit on the floor, connected to the Earth, in a circle with no beginning and no end. There tends to be a sacred space in the middle … When you're going into the circle, the purpose is not to convince anyone, it's just to show up. The beautiful thing about what happens is that people do get convinced. Usually, at the end, there's a vibe. There's almost a common narrative that gets constructed, because nobody's story is independent of the others, and the stories start to weave with each other. In the end, there is a common meaning that we found. Sometimes not in the first circle. Sometimes it takes a few times of being in circle before common meaning can emerge. And that’s ok! Not everything is or needs to be fast. Sometimes, in fact, most times, the process, the journey, the experience is the transformation. Being in circle ends up being a practice you embrace, not an occasion, but something that you continue to do as the way that you make meaning. You make meaning versus sharing meaning, and you make meaning together.”

This collective storying brings us back into a felt sense of the fabric of our places and disturbs the repeating patterns that exist within us as individuals, collectives and societies that perpetuate worldviews that hold us in separation, injustice, violence and degeneration. Practices such as these bring us back into our relationality.

Systemic worldviews are ever-emerging, rooted in multiple lineages, from traditional cultures and spiritual practices; the study of complexity within biology, physics, mathematics, cybernetics; permaculture and biomimicry; the social sciences and design innovation; and organisational change work and justice movements. Systemic ways of thinking, being and doing can entwine and coalesce, bringing forth worldviews rooted in multiple lineages. Melanie observes the diverse lineages she holds and states, “You can have separate and distinct lineages, and the space in between is an ethical space – it’s what Willie Ermine, a Cree scholar, called it, my Uncle Dan Longboat called it, a sacred space between different ways of knowing.”

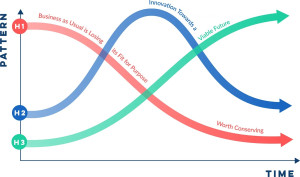

Contemplating the emergence of worldviews, Eruera shares, “One of the big shifts for me is how do we navigate loss and what are the things we need to let go of? For new to emerge, things need to die. In Maoridom, we have concepts like kia tukunga kua mai, in which we release something for it to be laid to rest, to replenish. There are ways in our language and in our culture, which we can acknowledge and let go of things with respect. I think one of the big challenges is how do we let old ways that aren't working for us die off so that we can free ourselves to embrace new ways of thinking and doing?”

This big question is what systems practitioners around the world are wrestling with, seeking deep change and systemic transformation that enables new vitality in our ways of thinking, being and acting and in our interconnected social, ecological, societal and planetary systems.

We extend heartfelt thanks to the practitioners for sharing their wisdoms, perspectives, thoughts and ideas.

With this, let us introduce the contributors to these emergent works:

In alphabetical order:

Ana Lucia Castaño Galvis is the co-founder of Arare Co., an organization that fosters regenerative development of primary production systems in Colombia and Mexico.

Ben Haggard specialises in a holistic, systems-based approach to understanding and building upon the complex human, natural and economic relationships that create and sustain the vitality and viability of a place. He is a founding member of Regenesis.

Constança Belchior is a facilitator and designer of innovation and systemic change with a background in natural sciences and sustainable policy making. She is co-founder of Lúcida, a change management organisation guided by a living change perspective.

Eruera Tarena is Executive Director at Tokona Te Raki, Māori Futures Collective in Aotearoa, an indigenous social innovation lab housed under the mana of Ngai Tahu and based in Otautahi/Christchurch.

Habiba Nabatu is Director of Practice at Lankelly Chase, a charitable foundation working to improve the quality of life of people who face severe and multiple disadvantage. She supports pioneering people and communities to nurture the ideas and relationships that can help improve the way we all approach social disadvantage.

Juanita Zerda is a Director at the Collective Change Lab, where she works to support individuals, communities and organizations in transforming inequitable and unjust systems, through more holistic and non-dominant collective change practices.

Lauren Hermanus is a sustainable development researcher and practitioner with 12 years of experience spanning the public and private sectors and academia. She works on issues of just transition, climate resilience, sustainable development, and the adaptive and anticipatory governance that underpins these dynamics.

Maya Narayan is the co-founder of Holon Perspectives, a Mumbai based consultancy, founded with a mission of developing the systems thinking ecosystem in India. She facilitates systems change workshops to better equip organisations and individuals, with tools and frameworks for solving complex problems.

Melanie Goodchild is an Anishinaabe (Ojibway) systems thinking and complexity scholar. She is part of the faculty at the Academy for Systems Change, the Presenting Institute’s u-school for Transformation and the Wolf Willow Institute for Systems Learning.

Tatenda Nzingha Mazowe is a specialised therapist, yogini, author, artist and hypnotist. She is the creator of Oshun Rises, a social enterprise and healing justice foundation committed to re-anchoring African Women's presence in alternative healing and wellness research.

with Rodrigo Bautista, Saskia Rysenbry, Sean Andrew and Anna Birney.