The context

Images

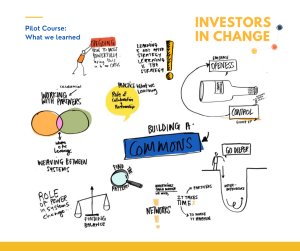

Isn’t it interesting how frequently as human beings we turn to metaphor? Sometimes these images are so embedded in the everyday that we don’t see them for what they are. We talk about ‘just ploughing on’, ‘turning over a new leaf’ and much more. Why? Because we don’t feel, think and communicate solely in mechanistic term, we are not ‘desiccated calculating machines’. We think in patterns, through resonance, emotion, stories and intuitive connection as well as logic.

Metaphor evokes in us things the literal cannot. It uses the poet’s deftness to reduce the messiness of the world, rejects the technocrat’s straight line sketch of reality. Metaphors also offer shortcuts to submerged mental models or situations, containing in their DNA bundles of previous inter-related experience and learning. I find images can be useful touchstones or motifs around which to organise my thoughts or re-centre activity or purpose. ‘Be more water’ etc.

Systems

Given this, it’s not surprising that imagery and metaphor feature heavily in systems thinking.

Over the past six months I’ve been learning about systems thinking approaches as well as systems change — their practical application in the cause of social justice or similar ends. I’ve been exposed to an intoxicating array of philosophies, tools, narratives and claims. Inevitably some have resonated more strongly than others. A couple I have found a bit vague (but probably didn’t understand) and a couple I have found a bit opaque (and definitely didn’t understand).

But the process of learning has been quite liberating. It has given me new ways to think about the universe I exist within; who can ask for more than that?

Imagine if a toolkit existed which allowed you to pick the lock of whatever complex policy or operational challenges you were dealing with that day. But also somehow captured the shifting beauty of a thousand starlings in flight or the majesty of the moss covered forest-as-organism. Something that gave definition and structure to all the intuitive system-craft we develop simply by being tenacious and creative in our work. That to me is the appeal of systems thinking.

Systems change in the everyday

Some of the approaches I have come to know take hard work, safeguarded time and the willing collaboration of colleagues. Others flit around at the paradigm level, triggering unconscious mindset micro-recalibrations. The variety is at times overwhelming.

So when I asked myself what artefact I wanted to produce to mark the end of my School of System Change Basecamp programme I thought I would consider practical ways to weave embed systemic practice into the everyday.

After reflection I concluded first one thing and then another. Firstly, that identifying and developing the mental and behavioural pre-conditions which allow systemic thinking to flourish is probably more important than striving to develop deep technical understanding of specific tools — after all no plants will grow in a barren field, no matter how packed with potential the seed. And secondly that I wanted to use emblematic metaphors to pin down the most important of these core attitudes, from which a number of simple, everyday systemic practices could then flow.

So the three sections below are a simple — and imperfect — attempt at that. Three images to lodge in my head, and perhaps yours too.

The images

Turning the stone

I have a memory as a child of turning a large flat stone in a wood and becoming enthralled at the universe-in-miniature beneath it. Insect life, leaf mulch, moss. The dynamic equilibrium of decay and fertility, death and life.

Although it’s impossible to pin down what systems thinking/change represents to any single person, for me it is a world-view build on a deep curiosity about the universe and our place in it. It’s hard to be open to other standpoints, learn or develop without an open mind (and an open heart too). A sense of ongoing intellectual and social inquiry can turbo-change any job which requires tactical relationship building, political weather reading, policy landscape navigating and hard decision making.

Ways to turn the stone:

- Deliberately immerse yourself in media and news sources you know you’ll disagree with. Take time to mentally articulate why you disagree with the arguments and be wary of jumping to conclusions. This is actually quite hard to do! The voluntary sector in the UK, for instance, has an obvious bias towards the soft left politically but I hear few people challenging the system to actively seek out opposing views and force the remaking of arguments for the full range of world-views. If you find your ideas shored up by the process that’s great — like a vital aircraft component that’s been stress-tested to near destruction in the workshop it is now ready for use in the outside world. However you may find your ideas slowly changing — it’s all part of ‘exposing your mental models to the light of day’ (Donella Meadows).

- ‘Get the beat of the system’ (DM again) — set up a rolling meeting with an inter-disciplinary cast representing the most obvious system viewpoints around which you are working. Or convene a space with four or five experts from the same discipline. Get a monthly Zoom/Team invite in the diary and the admin load is light. Help set the tone and model behaviour at the beginning then sit back — see what people bring. It’s amazing the insights, thoughts, ideas (and yes rants) people share, once they are convinced of the fact they are within a group of trusted system colleagues, outside the more formal spaces of government forums and rigid agendas. Sometimes this more explorative space may feel unfamiliar so you may need to sell it as an informal advisory group of some kind. Convening isn’t about just ‘doing the admin’ it’s about setting a tone, making people feel valued and respected, ‘holding the space’ and modelling behaviour that you wish to see others exhibit.

Building the spider’s web

There are three basic elements in any system — data points (people, perspectives, organisations, cells, trees), the connections between them and a uniting, animating purpose. My observation from policy work is that too much attention is paid to the things themselves and not enough to the connections between them.

Building a network of contacts — and entrepreneurially convening flexible spaces within it — may again allow you to get the beat of the system and develop a more richly detailed (though still partial) map of the territory. A fancy name for this might be ‘distributed cognition’, but I think of it as building a web.

Ways to build the web:

- At the most simple level it could be consciously focusing on the relational. Almost all roles and ways of exploring the world involve working with and through others so relationships are obviously key. Systems leadership across organisational boundaries is impossible without high-quality, sticky and trusting relationships. These will support all future work from developing shared campaign positions to negotiating the finances of a major joint operational undertaking. Thinking of relational workas the work and not just a means todoing the work might help.

- If getting into systems change feels a bit like joining a secret society then it follows that you must identify and cultivate your fellow travellers. They will not appear according to rank, status or job description. Some will be formally trained and others not. Carving out space and time is key here, which is why I’ve started some thinking about a systems change learning club with an emphasis on the fun, informal side of systems exploration.

Looking into the pond

Knowledge of self precedes almost all other forms of knowledge. The wisdom of the ages tells us that we must know ourselves before turning to identify problems and solutions in the external world — ‘physician, heal thyself’.

There is no two ways about it — to work systemically is to work reflectively. The whole idea is about taking a step back and what is that other than an instruction for reflection?

The image of a still pond reveals itself to me here. Mirror-like, but not a mirror. A surface broken by debris, imperfectly reflecting a face.

Ways to look into the pond:

- Building simple reflective practice into the everyday. Do you have a key series of meetings or a super important stakeholder relationships to develop? Or perhaps a colleague you are struggling to get on with? Or a knotty policy issue dancing before your eyes? Try journaling. Don’t overthink it, use a physical journal or a note-taking app like Evernote to get some stuff down. This is usually about the wisdom of the moment so try to do it immediately after the event rather than in hindsight (when our brains begin to impose post-hoc rationalisation). I remember doing this after my first board meeting and breaking it into ‘head’ and ‘heart’. The first covered the mental and bodily experience of a potentially stressful situation, the second provides analytic commentary on how events unfolded and how things could be different next time.

- The pond does not reflect just the individual but the system itself. One of the School for System Change’s systemic practices — which I love — is ‘enabling the system to see itself, hold the whole picture’. Think about the causal chains that (nominally at least) link the key data points within the system you are working on. For me it might be something like: minister is keen on a policy, directs senior officials; officials develop policy framework; resource devolved to local government level; commissioner commissions provider; provider CEO sets out a vision; ops director mobilises a service; practitioners make the magic happen for people in recovery; person in recovery volunteers as peer mentor. (You can make it more or less detailed as you see fit.) Now typically most data points (people in this instance) are familiar with only their neighbouring one or two points but much less so with the ones further up or down ‘the food chain’. Short-circuiting those connections can have powerful results. I recently organised a trip for a very senior civil servant who had taken on the treatment and recovery brief. We brought him, and other officials, to a recovery service in North London to listen and learn from senior public health representatives, local government commissioners, frontline workers and people in recovery. And in that room in Tottenham the system was presented with a mirror and — fleetingly — could see itself and understand its shared purpose. The officials walked away remembering that policy-making is not an end in itself but an embodiment of the social contract in action; communal resource being deployed to high quality create public services. The frontline workers walked away feeling that policymaking at the centre is hard, but has good people attempting to address that hardness. Things click into place. ‘Ah, I get why that join up with criminal justice doesn’t work properly, as you’ve had your budgets hammered’. ‘So that’s what assertive outreach is, I had always wondered’. ‘So which agencies should we try and bring together at a local level to provide accountability back to the centre?’ ‘I can see it now, this is why we do what we do — communities improved, families healed, citizens recovering connection and meaning’.

- Finally I hope the pond will reveal the embedded nature of our locations within multiple overlapping systems. And the see-sawing of feelings this realisation brings — greater understanding, identification of allies and experience of positive change delivering hope and a potent sense of agency on the one hand, awe at the scale and intricacies of the systems which shape the problems we wrestle with delivering a sense of hopelessness on the other. It might be daunting but we are part of it. As one of my co-learners brilliantly put it: ‘I am the system; we are the system’.